Ten students from Kashmir’s Srinagar stepped off their flight in Kerala’s Kozhikode on an October morning, blinking in the coastal humidity.

They came to visit a government school in Nadakkavu. Back home in Srinagar, like it is in much of India, government schools meant the last resort, the place where you went because private schools were unaffordable. Their own school, the government Girls Higher Secondary School (GHSS) in Kothibagh, could soon be an exception, having just finished a major renovation inspired by “the Nadakkavu model”. This trip to Kozhikode was to see first-hand what their school could eventually become.

Earlier this month, in a New Yorker interview, editor David Remnick posed a question to Zohran Mamdani, the 33-year-old socialist Democrat who is the frontrunner to be New York City’s next mayor, about the crisis in its public schools: How can we make our public education such that even if you have the means, it’s still where you choose to go? Is it a funding question, or something deeper?

The question probably finds an unlikely answer halfway across the world, in these two unlikeliest of Indian cities, 1,500 miles apart, in the snow-capped valley of Kashmir and the tropical sun of Kerala.

THE GOOD SCHOOL

At the government Vocational Higher Secondary School (VHSS), Nadakkavu, in the heart of Kozhikode city, it is not unusual to spot former students scaling the compound wall. They are not breaking in to steal or vandalise. They are trying to catch a glimpse of what they missed—renovated corridors, a new library, science labs. The drab school they attended has become something else entirely. Something where they would proudly send their children to.

The architect of this transformation and the similar one undergoing in Srinagar is Faizal E Kottikollon, a Dubai-based billionaire businessman, who hails from Kozhikode. His journey from steel scrap trade to school reform reads like a parable of modern capitalism finding its conscience. His father founded Peekaay Steel—which imports steel scraps from China, makes castings and supplies to US-based companies—a business so globally integrated that Gaza conflict and Red Sea piracy affect their bottom line.

Faizal, as he prefers to be referred to, built a steel foundry, Emirates Techno Casting, in UAE, transforming a polluting, red-category business into a green one, and sold it to Tyco International in 2011 for $400 million. He later founded the Dubai-headquartered conglomerate KEF Holdings. But wealth, he discovered, was merely a tool. “I made wealth through knowledge,” he says, “for which I thank the education system in Kerala.”

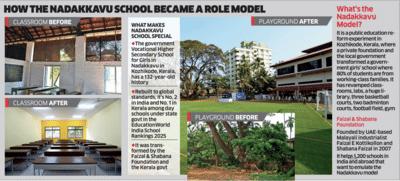

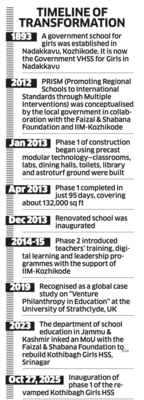

The Nadakkavu school experiment began in 2018 with a simple realisation that a parent wouldn’t send their children to a government school if they could. The infrastructure was crumbling, but more damaging was the cultural inferiority complex. Private schools with “posh, English-speaking students and clean corridors” had become aspirational totems.

Faizal decided to do something about it. He earmarked ₹16 crore to revamp the infrastructure, ₹7 crore for soft-skills development like teachers’ training, and partnered with the then MLA, Pradeep Kumar, a leader of the ruling Communist Party of India (Marxist), who chipped in with ₹5.5 crore from his development fund. Along with the then school principal, Beena Philip, they set out to reimagine what a public school could be.

Today, it’s a case study of what public infra can be with a little bit of imagination. Scottish architect William Cooper designed the corridors that invite lingering, reading corners that encourage contemplation and a library housing more than 25,000 books. The main hall, with high ceilings, doubles as the school’s social hub. The dining hall seats 2,000 students and serves both free meals and paid burgers. There are three basketball courts, two badminton courts, football and hockey fields with astroturf and a gym. All free.

More than 80% of its students come from working-class, if not poor, families. Their uniform includes a navy-blue coat, the kind seen in elite private schools. For children, this detail matters, it transforms things. Their parents and neighbours are seeing them in blazers for the first time. It gives them an identity beyond their economic circumstances.

The transformation has worked. The school that once struggled to fill classrooms now draws more than 2,000 students who travel from as far as 16 km. It is ranked the second-best school in India and the best in Kerala in the EducationWorld India School Rankings 2025, a national survey, in the category of state-funded day schools.

From next week, Bareen Rashid and Hibah Arshad from faraway Srinagar will be the latest beneficiaries of a silent school revolution that started in Kozhikode.

THE KASHMIR CHAPTER

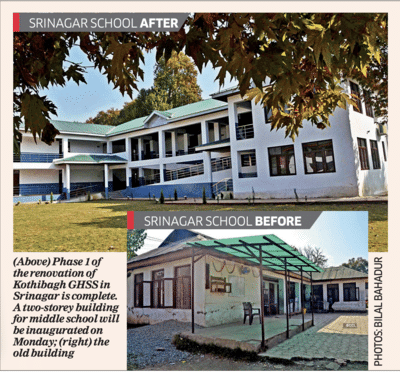

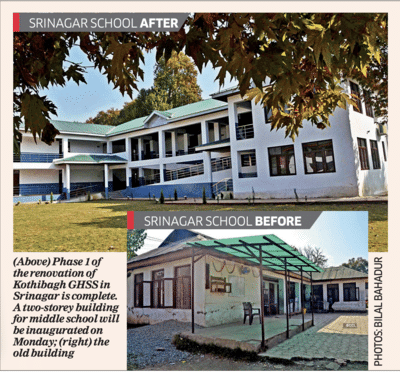

The GHSS Kothibagh in the heart of Srinagar’s business district of Lal Chowk has classes from kindergarten to XII. On October 27, J&K Lieutenant-Governor Manoj Sinha will inaugurate phase 1 of the renovation project, which includes a new two-storey building for the middle school. The next phase involves a new administration block and renovation of the higher secondary school buildings. The campus itself is undergoing a significant physical change with new buildings with modern facilities coming up.

Back on the Nadakkavu school campus, soaking in the sun, the visiting students from Kothibagh were more interested in the everyday Kerala story. “People are eating on banana leaves,” marvelled Rashid, carrying the wonder of someone discovering that the world could be organised differently. “They are carrying jute bags, how ecofriendly!” exclaimed Arshad.

The girl students from Kashmir, sitting in a semicircle, were still processing their second day in Kozhikode. They were surrounded by students who moved around in rhythms of daily life that felt fundamentally different. “Student ambassadors”, trained to guide the constant stream of visitors, approached each of them and walked them through the campus, carrying themselves with a confidence no curriculum could teach.

For three days, the Kashmiri students were in a school where the word “government” did not mean “neglect” and was instead a byword for quality, a source of pride.

“The school’s standing matters,” says Annet Irene Hermon, a Class XI student of Nadakkavu school. “When people learn I now go to Nadakkavu, it means something—the ranking, the facilities.” She adjusts her coat’s collar. “And wearing this... I feel different. I am more serious about my education. Like I’m part of something bigger.”

The Kashmiri students also met the mayor of the city who, as it happens, is the same Beena Philip, the school’s former principal. The other architect of the project, former MLA Pradeep Kumar, is the chief minister’s political secretary. Good education, it seems, generates political capital.

“Do you know Vasco da Gama?” Philip asked them. The students knew—the Portuguese explorer whose arrival in Calicut (Kozhikode) in 1498 marked the beginning of European colonisation of India. The conversation moved to their school in Srinagar. Arshad, a Class IX student at Kothibagh, recalled the warmth of that conversation: it is like everyone here cared about what would happen to their school. It is like they wanted her to succeed. It is like they were invested in her transformation.

Kerala’s school transformation project, officially called PRISM (Promoting Regional Schools to International Standards through Multiple Interventions), is being expanded to other institutions, with a budgeted outlay of ₹1,000 crore from the state government. Meanwhile, the Faizal and Shabana Foundation (FSF), co-founded by Faizal and his wife Shabana, is taking that change beyond Kerala. FSF has spent ₹250 crore on this experiment in multiple cities. Apart from the full-scale transformation of schools in Nadakkavu and Kothibagh, it supports infrastructure development in 10 schools in Kerala, one each in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu as well as two in Uganda and one in Kenya. It is also hand-holding 1,200 schools that want to emulate the Nadakkavu model.

THE CHINAR SEED

Faizal thought of transplanting the Nadakkavu success to Kashmir when he visited Srinagar in 2020, a year after the abrogation of Article 370. He was part of a UAE business delegation exploring investment opportunities; it was his first visit to Kashmir.

Faizal took a shikara across the Dal Lake and talked to people along the banks and in the market. The delegation’s focus was retail spaces, luxury brands—the usual markers of development. But as Faizal talked to people, he heard a different set of complaints—about the lack of healthcare facilities and failing public schools. They needed, he thought, schools more than shopping complexes.

He met with Lieutenant-Governor Sinha and showed him a video of Nadakkavu school’s transformation. “What can you do for us?” Sinha asked. “I told him: Give me one school,” recalls Faizal. “It can be replicated across Jammu and Kashmir.”

Sinha bought into the idea. They chose the government GHSS in Kothibagh. There were 10,400 students in the area but GHSS Kothibagh had only 140 students in KG to Class X. Most of the children went to private schools. They shifted to state schools only for Classes XI and XII. The Kothibagh school’s renovation, which would cost ₹20 crore, began in 2021.

However, the most consequential intervention, according to Faizal, is the exchange programme under which the students came to Kozhikode. “These kids never go out of Kashmir,” he says. “These students represent the first batch of young leaders who want transformation. This initiative is not a one-time effort but a regular, sustained engagement.”

OVER TO KOTHIBAGH

Standing amid flaming chinar trees in Kothibagh, principal-in-charge Sabahat Chalkoo is thrilled about the new life her school is about to get. “It is an amazing intervention that fills the gaps in a government school. We are a prestigious school and this initiative gives us wings to fly,” she says.

The new building will have air-conditioned classrooms and robotics and STEM laboratories. All the buildings are differently-abled-friendly. Students will get to work on electronic circuits, chips, sensors and drones. FSF signed a memorandum of understanding with the J&K government in 2023 and has since conducted at least six training sessions for teachers.

“We were exposed to multifaceted learning approaches and trained to mentor students in the best possible ways,” says Maryam Akbar, a senior lecturer, who teaches geography. She was part of the group that visited Nadakkavu school. “In Kerala, communities are strong stakeholders in public schools, which makes the whole system accountable and accessible to students.”

Her colleague, Humaira Shah, who teaches environmental sciences, says the atmosphere in Kerala, in and around the school, was “vibrant and hopeful”. Zahoor Ahmad Sheikh, the coordinator of the renovation project, says their Kerala experience both revealed and magnified the necessity of going beyond the traditional educational experience. “We need to own our institutions as well as the students and go beyond rote learning,” he says.

Khairat Muhammad, a retired teacher, adds a caveat: “Such philanthropic efforts need to be under scrutiny to deliver the results they are meant to. They shouldn’t fall prey to bureaucratic routines and red tape,” he says.

Young Arshad hopes that the students in the government schools in Kashmir will have the same opportunities and exposure available to students in Kerala. Arshad says she won’t forget their days in Kozhikode.

VALUE OF EXCHANGE

On their last day, their new friends from Kerala gave two traditional dance performances, oppana and kaikottikali, as a farewell piece. The teenagers from Srinagar demonstrated Kashmiri folk steps. Then they attempted Kerala’s classical mudras or hand gestures while their hosts learned theirs. It was the kind of evening where differences became points of connection, through curiosity, through laughter, through the simple act of trying to understand the other’s traditions.

However, the faces of the Kashmiri children shifted when they were asked if the Pahalgam attack—in which 26 civilians were killed and which set off an India-Pakistan military conflict—had any impact on their schooling. “We go to school like any other kid anywhere else in India,” a student said, her voice gaining an edge. “We don’t have daily shutdowns.” The group became animated.

Kashmir is beautiful, they insisted. Peaceful, too. One of the elders travelling with them invited Malayalis to come and see for themselves. The others clapped.

The students made it look like they didn’t carry the trauma of decades of turmoil that defined previous generations. They scroll Instagram, watch Netflix. Their identities, they insisted, belong to a shared modern consciousness that transcends geography.

In the evening, they went to the beach. The moment they saw the sea, they all jumped out—they ran, got wet, built sandcastles. The kind of things kids do when they are on a beach.

The Nadakkavu students asked about snow, the Dal Lake, what winter felt like in the mountains. The Srinagar students asked about monsoons, about how differently humidity hit on the coast. The abstract, grand phrases used to describe their respective states—Heaven on Earth, God’s Own Country—collapsed into specifics: what does snow feel like, melting in your palm; does humidity make it hard to breathe?

When asked if they would change anything about Kerala, the Kashmiri students found nothing wanting, nothing that needed fixing. One student smiled and said: “Maybe the weather.” The kind of joke that lands differently in a place where kids have stopped believing in limits.

They came to visit a government school in Nadakkavu. Back home in Srinagar, like it is in much of India, government schools meant the last resort, the place where you went because private schools were unaffordable. Their own school, the government Girls Higher Secondary School (GHSS) in Kothibagh, could soon be an exception, having just finished a major renovation inspired by “the Nadakkavu model”. This trip to Kozhikode was to see first-hand what their school could eventually become.

Earlier this month, in a New Yorker interview, editor David Remnick posed a question to Zohran Mamdani, the 33-year-old socialist Democrat who is the frontrunner to be New York City’s next mayor, about the crisis in its public schools: How can we make our public education such that even if you have the means, it’s still where you choose to go? Is it a funding question, or something deeper?

The question probably finds an unlikely answer halfway across the world, in these two unlikeliest of Indian cities, 1,500 miles apart, in the snow-capped valley of Kashmir and the tropical sun of Kerala.

THE GOOD SCHOOL

At the government Vocational Higher Secondary School (VHSS), Nadakkavu, in the heart of Kozhikode city, it is not unusual to spot former students scaling the compound wall. They are not breaking in to steal or vandalise. They are trying to catch a glimpse of what they missed—renovated corridors, a new library, science labs. The drab school they attended has become something else entirely. Something where they would proudly send their children to.

The architect of this transformation and the similar one undergoing in Srinagar is Faizal E Kottikollon, a Dubai-based billionaire businessman, who hails from Kozhikode. His journey from steel scrap trade to school reform reads like a parable of modern capitalism finding its conscience. His father founded Peekaay Steel—which imports steel scraps from China, makes castings and supplies to US-based companies—a business so globally integrated that Gaza conflict and Red Sea piracy affect their bottom line.

Faizal, as he prefers to be referred to, built a steel foundry, Emirates Techno Casting, in UAE, transforming a polluting, red-category business into a green one, and sold it to Tyco International in 2011 for $400 million. He later founded the Dubai-headquartered conglomerate KEF Holdings. But wealth, he discovered, was merely a tool. “I made wealth through knowledge,” he says, “for which I thank the education system in Kerala.”

The Nadakkavu school experiment began in 2018 with a simple realisation that a parent wouldn’t send their children to a government school if they could. The infrastructure was crumbling, but more damaging was the cultural inferiority complex. Private schools with “posh, English-speaking students and clean corridors” had become aspirational totems.

Faizal decided to do something about it. He earmarked ₹16 crore to revamp the infrastructure, ₹7 crore for soft-skills development like teachers’ training, and partnered with the then MLA, Pradeep Kumar, a leader of the ruling Communist Party of India (Marxist), who chipped in with ₹5.5 crore from his development fund. Along with the then school principal, Beena Philip, they set out to reimagine what a public school could be.

Today, it’s a case study of what public infra can be with a little bit of imagination. Scottish architect William Cooper designed the corridors that invite lingering, reading corners that encourage contemplation and a library housing more than 25,000 books. The main hall, with high ceilings, doubles as the school’s social hub. The dining hall seats 2,000 students and serves both free meals and paid burgers. There are three basketball courts, two badminton courts, football and hockey fields with astroturf and a gym. All free.

More than 80% of its students come from working-class, if not poor, families. Their uniform includes a navy-blue coat, the kind seen in elite private schools. For children, this detail matters, it transforms things. Their parents and neighbours are seeing them in blazers for the first time. It gives them an identity beyond their economic circumstances.

The transformation has worked. The school that once struggled to fill classrooms now draws more than 2,000 students who travel from as far as 16 km. It is ranked the second-best school in India and the best in Kerala in the EducationWorld India School Rankings 2025, a national survey, in the category of state-funded day schools.

From next week, Bareen Rashid and Hibah Arshad from faraway Srinagar will be the latest beneficiaries of a silent school revolution that started in Kozhikode.

THE KASHMIR CHAPTER

The GHSS Kothibagh in the heart of Srinagar’s business district of Lal Chowk has classes from kindergarten to XII. On October 27, J&K Lieutenant-Governor Manoj Sinha will inaugurate phase 1 of the renovation project, which includes a new two-storey building for the middle school. The next phase involves a new administration block and renovation of the higher secondary school buildings. The campus itself is undergoing a significant physical change with new buildings with modern facilities coming up.

Back on the Nadakkavu school campus, soaking in the sun, the visiting students from Kothibagh were more interested in the everyday Kerala story. “People are eating on banana leaves,” marvelled Rashid, carrying the wonder of someone discovering that the world could be organised differently. “They are carrying jute bags, how ecofriendly!” exclaimed Arshad.

The girl students from Kashmir, sitting in a semicircle, were still processing their second day in Kozhikode. They were surrounded by students who moved around in rhythms of daily life that felt fundamentally different. “Student ambassadors”, trained to guide the constant stream of visitors, approached each of them and walked them through the campus, carrying themselves with a confidence no curriculum could teach.

For three days, the Kashmiri students were in a school where the word “government” did not mean “neglect” and was instead a byword for quality, a source of pride.

“The school’s standing matters,” says Annet Irene Hermon, a Class XI student of Nadakkavu school. “When people learn I now go to Nadakkavu, it means something—the ranking, the facilities.” She adjusts her coat’s collar. “And wearing this... I feel different. I am more serious about my education. Like I’m part of something bigger.”

The Kashmiri students also met the mayor of the city who, as it happens, is the same Beena Philip, the school’s former principal. The other architect of the project, former MLA Pradeep Kumar, is the chief minister’s political secretary. Good education, it seems, generates political capital.

“Do you know Vasco da Gama?” Philip asked them. The students knew—the Portuguese explorer whose arrival in Calicut (Kozhikode) in 1498 marked the beginning of European colonisation of India. The conversation moved to their school in Srinagar. Arshad, a Class IX student at Kothibagh, recalled the warmth of that conversation: it is like everyone here cared about what would happen to their school. It is like they wanted her to succeed. It is like they were invested in her transformation.

Kerala’s school transformation project, officially called PRISM (Promoting Regional Schools to International Standards through Multiple Interventions), is being expanded to other institutions, with a budgeted outlay of ₹1,000 crore from the state government. Meanwhile, the Faizal and Shabana Foundation (FSF), co-founded by Faizal and his wife Shabana, is taking that change beyond Kerala. FSF has spent ₹250 crore on this experiment in multiple cities. Apart from the full-scale transformation of schools in Nadakkavu and Kothibagh, it supports infrastructure development in 10 schools in Kerala, one each in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu as well as two in Uganda and one in Kenya. It is also hand-holding 1,200 schools that want to emulate the Nadakkavu model.

THE CHINAR SEED

Faizal thought of transplanting the Nadakkavu success to Kashmir when he visited Srinagar in 2020, a year after the abrogation of Article 370. He was part of a UAE business delegation exploring investment opportunities; it was his first visit to Kashmir.

Faizal took a shikara across the Dal Lake and talked to people along the banks and in the market. The delegation’s focus was retail spaces, luxury brands—the usual markers of development. But as Faizal talked to people, he heard a different set of complaints—about the lack of healthcare facilities and failing public schools. They needed, he thought, schools more than shopping complexes.

He met with Lieutenant-Governor Sinha and showed him a video of Nadakkavu school’s transformation. “What can you do for us?” Sinha asked. “I told him: Give me one school,” recalls Faizal. “It can be replicated across Jammu and Kashmir.”

Sinha bought into the idea. They chose the government GHSS in Kothibagh. There were 10,400 students in the area but GHSS Kothibagh had only 140 students in KG to Class X. Most of the children went to private schools. They shifted to state schools only for Classes XI and XII. The Kothibagh school’s renovation, which would cost ₹20 crore, began in 2021.

However, the most consequential intervention, according to Faizal, is the exchange programme under which the students came to Kozhikode. “These kids never go out of Kashmir,” he says. “These students represent the first batch of young leaders who want transformation. This initiative is not a one-time effort but a regular, sustained engagement.”

OVER TO KOTHIBAGH

Standing amid flaming chinar trees in Kothibagh, principal-in-charge Sabahat Chalkoo is thrilled about the new life her school is about to get. “It is an amazing intervention that fills the gaps in a government school. We are a prestigious school and this initiative gives us wings to fly,” she says.

The new building will have air-conditioned classrooms and robotics and STEM laboratories. All the buildings are differently-abled-friendly. Students will get to work on electronic circuits, chips, sensors and drones. FSF signed a memorandum of understanding with the J&K government in 2023 and has since conducted at least six training sessions for teachers.

“We were exposed to multifaceted learning approaches and trained to mentor students in the best possible ways,” says Maryam Akbar, a senior lecturer, who teaches geography. She was part of the group that visited Nadakkavu school. “In Kerala, communities are strong stakeholders in public schools, which makes the whole system accountable and accessible to students.”

Her colleague, Humaira Shah, who teaches environmental sciences, says the atmosphere in Kerala, in and around the school, was “vibrant and hopeful”. Zahoor Ahmad Sheikh, the coordinator of the renovation project, says their Kerala experience both revealed and magnified the necessity of going beyond the traditional educational experience. “We need to own our institutions as well as the students and go beyond rote learning,” he says.

Khairat Muhammad, a retired teacher, adds a caveat: “Such philanthropic efforts need to be under scrutiny to deliver the results they are meant to. They shouldn’t fall prey to bureaucratic routines and red tape,” he says.

Young Arshad hopes that the students in the government schools in Kashmir will have the same opportunities and exposure available to students in Kerala. Arshad says she won’t forget their days in Kozhikode.

VALUE OF EXCHANGE

On their last day, their new friends from Kerala gave two traditional dance performances, oppana and kaikottikali, as a farewell piece. The teenagers from Srinagar demonstrated Kashmiri folk steps. Then they attempted Kerala’s classical mudras or hand gestures while their hosts learned theirs. It was the kind of evening where differences became points of connection, through curiosity, through laughter, through the simple act of trying to understand the other’s traditions.

However, the faces of the Kashmiri children shifted when they were asked if the Pahalgam attack—in which 26 civilians were killed and which set off an India-Pakistan military conflict—had any impact on their schooling. “We go to school like any other kid anywhere else in India,” a student said, her voice gaining an edge. “We don’t have daily shutdowns.” The group became animated.

Kashmir is beautiful, they insisted. Peaceful, too. One of the elders travelling with them invited Malayalis to come and see for themselves. The others clapped.

The students made it look like they didn’t carry the trauma of decades of turmoil that defined previous generations. They scroll Instagram, watch Netflix. Their identities, they insisted, belong to a shared modern consciousness that transcends geography.

In the evening, they went to the beach. The moment they saw the sea, they all jumped out—they ran, got wet, built sandcastles. The kind of things kids do when they are on a beach.

The Nadakkavu students asked about snow, the Dal Lake, what winter felt like in the mountains. The Srinagar students asked about monsoons, about how differently humidity hit on the coast. The abstract, grand phrases used to describe their respective states—Heaven on Earth, God’s Own Country—collapsed into specifics: what does snow feel like, melting in your palm; does humidity make it hard to breathe?

When asked if they would change anything about Kerala, the Kashmiri students found nothing wanting, nothing that needed fixing. One student smiled and said: “Maybe the weather.” The kind of joke that lands differently in a place where kids have stopped believing in limits.

You may also like

NYC mayoral race: Faith leaders representing over 150 congregations back Andrew Cuomo

Lando Norris fires dig at Ferrari while sat between Lewis Hamilton and Charles Leclerc

Dalip Tahil says he missed the chance to speak with Satish Shah due to his outdoor shoot

Traders allege e-commerce, quick commerce firms are violating norms

Lahore tops world's pollution chart as AQI hits hazardous 412, authorities launch crackdown